Redis Job Queue - Reloaded

In How to implement a job queue with Redis, we explained how to implement a job queue mechanism with Redis and the new Redis API from Quarkus. The approach explored in that blog post had a significant flaw: if the execution of a job failed, the request was lost and will never be re-attempted.

In this post, we explain how to improve the reliability of the job queue to handle failures, enable retry and use a dead-letter queue to avoid poison pills.

Recap & Problem

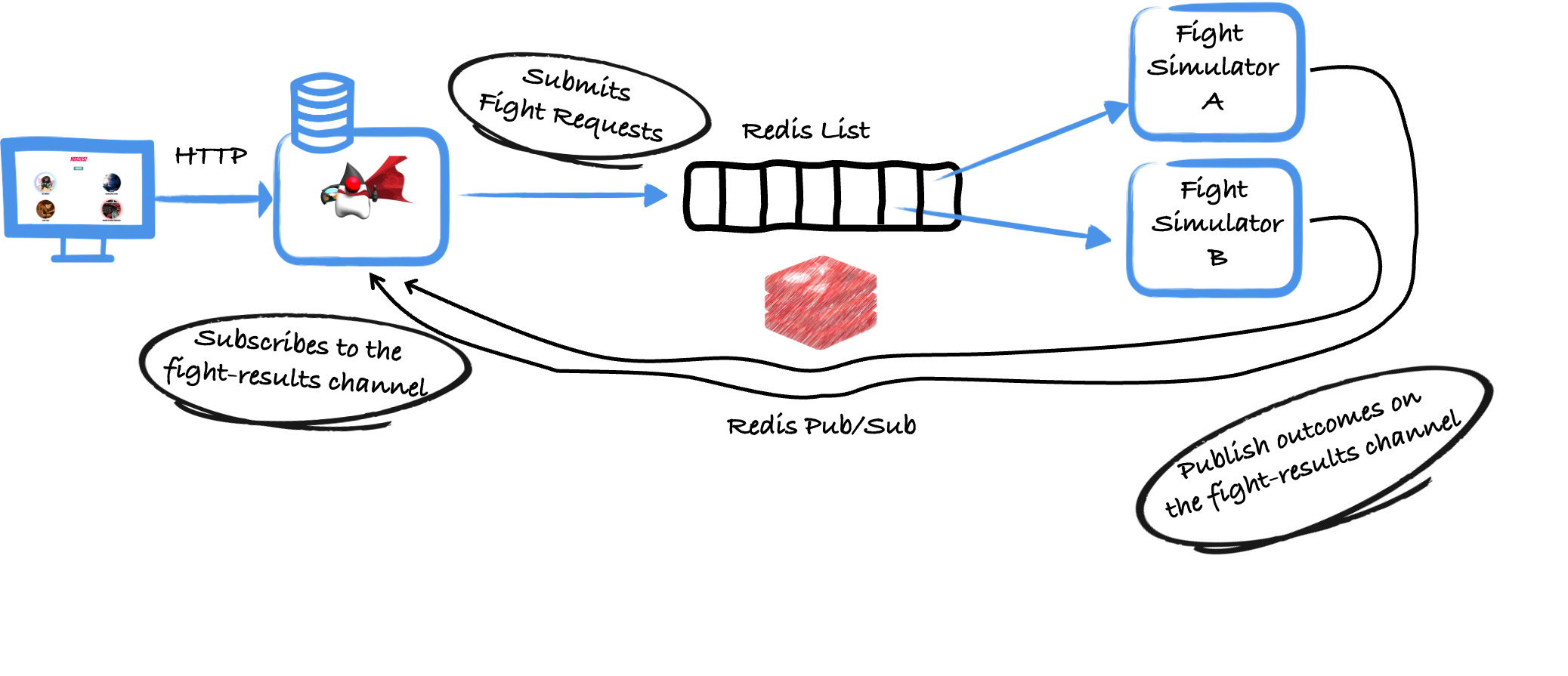

In the previous blog post, we implemented the following system.

An application receives fight requests and writes these requests into a Redis list. Several simulators processed this list. The outcomes of the fights were communicated using Redis Pub/Sub.

The architecture works and ensures that a fight can only be executed once, thanks to the brpop command used by the simulator code.

This command pops the item from the queue in an atomic manner and ensure that the other simulators can’t process it too.

However, this architecture has a drawback. If the processing of the popped fight request fails, the request is lost. No other simulator would be able to process it, and if the simulator that failed restarts, it will not reprocess the same request.

Introducing more queues

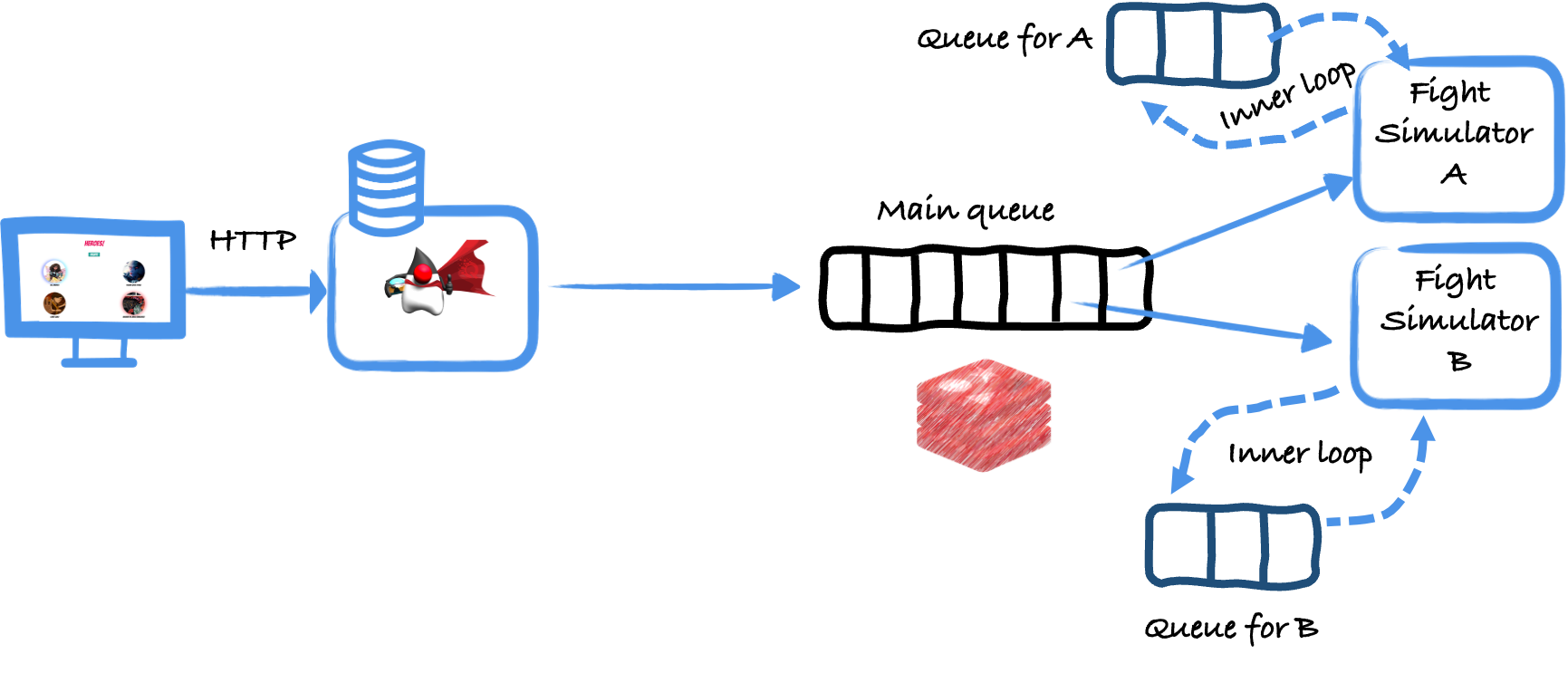

An approach to handle that problem is to introduce more queues. In addition to the main queue (the Redis list from the image above), we introduce one queue per simulator. Thus, each simulator has its private queue.

These private queues form a safety net.

So, the simulator does use not only the main queue but also its private queue:

this.queues = ds.list(FightRequest.class);

this.queueName = "queue-" + name; // the name of the private queueWhen a simulator pops a request from the main queue, it does not process it immediately; it writes it to its private queue.

To achieve this, we cannot use brpop and then write to the other queue, as if something wrong happens in between, we would have the same problem.

Instead, we use blmove, which pops an element from a list and pushes it into another in an atomic fashion.

Thus, we ensure that multiple simulators cannot consume the same request and that the request cannot be lost.

So, we use the following code to move the request from the main queue to the private queue:

// pop the item at the right side of the 'fight-requests' queue

// and writes it to the left side of 'queueName'.

// it returns the moved item or `null` in the entry queue, 'fight-requests',

// does not have any item, even after the 1-second delay

var moved = queues.blmove("fight-requests", queueName,

Position.RIGHT, Position.LEFT, Duration.ofSeconds(1));Now, the simulator does not simulate the requests from the main queue but needs to process the ones added to its private queue.

public void processRequestFromPrivateQueue() {

var request = queues.lindex(queueName, -1);

while (request != null) {

runSimulation(request);

queues.lrem(queueName, 1, request);

request = queues.lindex("queue-" + name, -1);

}

}This code is slightly different from the code from the previous blog.

This time, we do not pop.

We get the last item from the queue (index -1 is the last one), process it, and then remove it from the queue.

We do this until the queue is empty.

Let’s put everything together: 1. when the simulator starts, it should process the items from its private queue. So, if it crashes, it will retry to process the item. 2. once the private queue is empty, it gets new requests from the main queue. It will not process them directly but re-trigger the processing of the private queue until the queue is empty.

@Override

public void run() {

// First, check if we are recovering, and drain the requests from the

// simulator's queue

processRequestFromPrivateQueue();

while (! stopped) {

// Simulator's queue drained - poll the main queue

var moved = queues.blmove("fight-requests", queueName,

Position.RIGHT, Position.LEFT, Duration.ofSeconds(1)

);

if (moved != null) {

// If an element has been moved, process it

processRequestFromPrivateQueue();

}

}

}New architecture, new problems

That approach fixes the initial problem. If the processing fails, we retry it (as the request is not removed from the private queue). That will handle transient failures pretty well.

However, it also has its own set of drawbacks:

-

Duplicates: if the processing succeeds, but the

lremfails for any reason (like a network failure), the request will be processed another time as it was not removed from the queue. -

Poison pill: if a request cannot be processed successfully, it will retry to process it forever.

De-duplication

Handling duplicates require having a way to identify the requests uniquely and deduplicate manually. In other words, if all our requests have a unique id, we can check if that id has already been processed (for example, by storing the processed ids in another list or a hash). If the item has already been processed, ignore it (remove it from the queue) and process it to the next one:

public void processRequestFromPrivateQueue() {

var request = queues.lindex(queueName, -1);

while (request != null) {

if (! isDuplicate(request)) {

runSimulation(request);

}

queues.lrem(queueName, 1, request);

. request = queues.lindex("queue-" + name, -1);

}

}Avoiding swallowing the poison pill

Handling poison pills is more complex. A poison pill is a request that will always make the processing fails. It can be because of a bug in the processing code or something unexpected; it will always fail. Retrying, in this case, will not help; we are not facing a transient issue.

So, what can we do? We need to track the number of processing attempts for that request, and if it exceeds a specific number, let’s face it: we won’t be able to handle the request. We generally want to send the request to a dead-letter queue (DLQ), i.e., a specific queue storing the unprocessable items:

public void processRequestFromPrivateQueue() {

var request = queues.lindex(queueName, -1);

while (request != null) {

if (counter.incr(counterName) > MAX_ATTEMPT) {

// Give up - it's a poison pill

queues.lpush(DLQ, request); // Add to DLQ

} else {

runSimulation(request);

}

request = queues.lindex("queue-" + name, -1);

queues.lrem(queueName, 1, request);

counter.set(counterName, 0); // Reset

}

}The counter is a specific Redis integer value that we increment and reset once we succeed or give up.

The items from the DLQ are not lost; they are saved for future processing. These items could be re-added to the main queue (to verify if it was not a transient issue or the bug was fixed). Another approach requires that a human administrator looks at these requests before re-injecting them into the system; maybe it was just a formatting issue…

Summary

This post explores how to improve the job queue we implemented in How to implement a job queue with Redis. This initial implementation, while simple, would lose requests if the processing fails. This post proposes another, more complex, architecture to handle that case but also handle duplicates and poison pills. But, nothing comes for free, and the resulting code is slightly more complex.

Remember: Redis is a fantastic toolbox. But, it’s a toolbox; you build what you need with it, as it is rarely available out of the box. That being said, the richness of the Redis commands lets you do many things… (spoiler: we will see some of these things in future posts).